(CBC, 2023b)

Ko’jua

Mi’kmaq “dance of vigour”

-George Paul

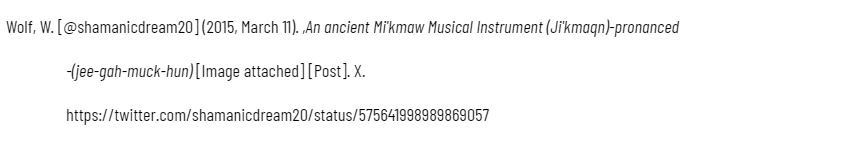

Land Acknowledgement

In the spirit of Reconciliation, we acknowledge that the land upon which we gather is unceded Mi’kmaq territory. Epekwitk (Prince Edward Island), Mi’kma’ki, is covered by the historic Treaties of Peace and Friendship. We pay our respects to the Indigenous Mi’kmaq People who have occupied this Island for over 13,000 years; past, present and future. We recognize the responsibility to educate ourselves and foster an environment of acceptance and inclusion.

We are all treaty people.

(L’nuey, 2021)

Pjila'si (Welcome)

Welcome to our virtual exhibit about the Mi’kmaq dance, Ko’jua. This learning resource is intended to give an overview of the importance of the cultural dance, Ko’jua, as we feel it is underrepresented online. We hope you enjoy learning about the impact this dance has had on the Indigenous people of the Maritimes. We encourage you to explore further the resources used to compile this exhibit and continue learning about the culture of the Mi’kmaq people.

Kwe’ Teluisi (Hello My Name Is)

Laurie Guindon

Laurie is a student of Ontario Tech University’s Bachelor of Arts in Education Studies. Originally from Ontario, she lives on Prince Edward Island (Epekwitk, Mi’kma’ki) with her husband and two children. She enjoys spending time in nature with her family and learning about the land and culture. Laurie aspires to ensure that cultural respect and recognition is inherent in all future education.

Kishola Levine

Kishola is a student of Ontario Tech University’s Bachelor of Arts in Education Studies. She was born and raised on the island of Grenada before migrating to Canada in 2014. Kishola now lives in Oshawa, Ontario, where she enjoys visiting local hidden gems within the Durham Region to learn more about the Canadian identity and culture.

Valerie English

Valerie is a student of Ontario Tech University’s Bachelor of Arts in Education Studies. She was born and raised in Stratford ON. She now lives in Owen Sound with her partner and her son where she enjoys spending time outdoors hiking and swimming. Valerie is located on the traditional lands Anishinabek Nation: the People of the Three Fires known as the Ojibwe, Odawa and Pottawatomie Nations. Also the Saugeen First Nation, and the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation, known collectively as the Saugeen Ojibway Nation.

History of Mi’kmaq

The Mi’kmaq (Mi’Kmaw) are the largest group of first nations people to originally occupy the Atlantic Provinces of Canada, traditionally known as Mi’kma’ki (Mi’gma’gi).

Mi’kmaq have occupied these lands for over 13,000 years

Mi’kma’ki is host to 29 Mi’kmaq nations

(CBC, 2023a)

Mi’kma’ki territory includes Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Quebec, PEI, and Maine

(The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2008b)

Mi’kmaq Lived a Nomadic Lifestyle

During the winter season, the Mi’kmaq lived in conical houses hunting for meat, and in the summer, they lived in oblong homes in the open-air, fishing and hunting seals. Mi’kmaq taught history through stories told by legends, helping them learn about their past. This is how they maintained their routes for the best fishing and hunting spots. Mi’kmaq were highly attuned to the land and the interconnectedness of plants, animals, watersheds, river systems and geology.

(The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2008b)

(Nova Scotia Archives, n.d.d)

(Nova Scotia Archives, n.d.b)

Mi’kmaq Regalia

Mi’kmaq clothing was made from any material that was readily accessible, such as animal skin and fur from deer and moose. They sewed clothing using needles made from deer bones. Their clothing represented social status, and the chiefs wore the most decorated garments.

(Nova Scotia Archives, n.d.c)

(Nova Scotia Archives, n.d.a)

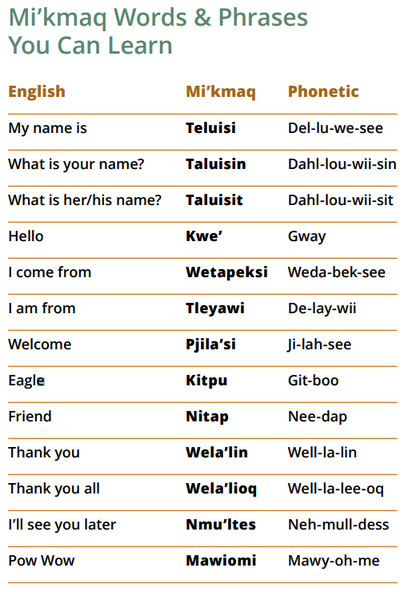

Mi’kmaw is the official first language of Nova Scotia

Mi’kmaw, is an Eastern Algonquin language

Mi’kmaq (meeg-gah-mah) comes from the root word Ni’kmaq (nee-gah-mah) meaning my kin/my relations. It is plural, referring to the larger group of people and/or the collective tribe of people. Mi’kmaq is not used as an adjective, nor is it a singular noun.

• Mi’kmaq: Mi’kmaq attend this school. Mi’kmaq live in this territory.

Mi’kmaw (meeg-gah-maw) comes from the root word Mi’kmaq. However, it is used as a singular noun or adjective.

• Mi’kmaw singular: He is Mi'kmaw. I am Mi’kmaw.

• Mi’kmaw adjective: The Mi’kmaw community.

Mi’kmaw Mawiomi.

L’nu (ull-new) is an ancient term that aligns with Nilnu (nilnew) meaning my tongue. It refers to the ability to speak the same tongue, or language. L’nu in short refers to “the people”, i.e., the people who speak the same language. Much like the term Mi’kmaw, L’nu is a singular noun or an adjective.

• L’nu singular: He is L’nu. I am L’nu. There is only one L’nu in the room.

• L’nu adjective: She has a L’nu wife. The L’nu community. L’nu Mawiomi

Mi’kmaq talking Dictionary

(Treaty Education Nova Scotia, 2023)

Mi’kmaq Continue to Honour Many Treaties

The Mi’kmaq are related to numerous Algonquian-speaking nations. “The Abenaki, Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and Wolastoqiyik make up the Wabanaki Confederacy, also known as the “People of the dawn”. As a confederacy, the Wabanki made treaties with other nations long before the arrival of settlers. Although, these traditional treaties were made of beads that formed images and designs outlining the agreements held within the treaty. These treaties are known as L'napsku'l - wampums” (Treaty Education Nova Scotia, 2023)

(L’nuey PEI, 2021)

History of Ko’jua

Ko’jua is a celebration dance of unknown origins. Evidence of the dance dates back to the 1800s, but many say it is much older than that, calling it “pre-contact”.

Ko’jua is a dance that is practiced solely by mi’kmaq

l’nuey, (2021)

(Mi’kmaq FineArts, 2017b)

Ko’jua is a generational dance that has been passed down through elders sharing their ways of knowing.

Ko’jua has traditionally been danced for many occasions including:

- Celebrations

- Weddings

- Ko’jua Socials

- Mawio'mi (powwows)

- Gatherings

- Births

- Hunting

- War

“When I dance, you can tell which family I'm from, from the way I dance.”-Michael R. Denny

Dance

Ko’jua has variations in the dance that are specific to certain Mi’kmaq families and communities.

The dance usually only lasts one minute owing to the fast tempo

Ko’jua is danced in a circle by taking three stomping steps while shuffling the opposite foot behind, then switching to the opposite feet and repeating.

(Mi’kmaq FineArts, 2017a)

“It has been said that before they placed the big wigwam (encampment for the Grand Chief), our ancestors used to dance the ko’jua on this particular spot. As a result of continuous dancing, the imprint of our peoples dancing could be seen on that same spot in a circular shape” -Michael R. Denny

(Stoney Bear, 2019)

Song

Ko’jua has more than 15 variations of songs that continue to evolve as the Mi’kmaq culture evolves. Common variations include:

- "Jukwa'lu'k Kwe'ji'ju'ow" or "Bring Your Little Sister"

- ‘Wapikatji'j" or "The Little White-Footed Dog"

- "Plawejuey" or "The Partridge Song"

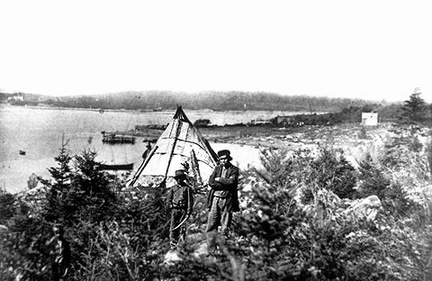

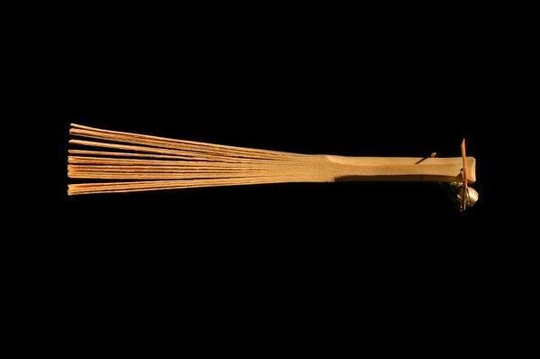

Ji’kmaqn

A Ji’kmaqn is a traditional instrument used to produce the sounds that accompany the Ko’jua dance. The term Ji’kmaqn refers to the sound produced by sticks beaten together. The instrument is created from black ash trees using remaining materials from basket splint production. The wood is pounded with a mallet and splits to create the “fan-like” instrument.

The Ji’kmaqn is made and used by only the Mi’kmaq people.

In times when Indigenous culture was forbidden, a Ji’kmaqn was easy to hide in the forest or a wood pile.

(X, 2015)

Hand Drum

Today, Ko’jua is more often accompanied by a traditional Mi’kmaq hand drum.

Mi’kmaq hand drums are crafted with a wealth of tradition and knowledge, incorporating aspects of the Medicine Wheel like North, East, South, and West, and the four spirits of the cedar, deer, moose, and human.

(Canadian Museum of History, n.d.)

Sharing Ko’jua

(Guindon, 2023)

Learn about the cultural impacts of Ko’jua on Alicia, Kaelyn, and Stephenson from the Native Council of Prince Edward Island in Epekwitk (Prince Edward Island), Mi'kma'ki.

Dance with Aluk

(CBC Kids, 2023)

Listen to Brittany

(IWK Health, 2021)

Sing with Morgan

(Toney, 2020)

Learn with Pikto'l

(Sprig Learning, 2022)

Influential Figures in Ko’jua Today

(Mi’kmaw Kina’matnewey, n.d.)

Michael R. Denny

Michael R. Denny is a notable traditional singer from the Eskasoni Mi’kmaw Nation on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Michael is passionate about reviving Mi’kmaw dances, songs, and language. Michael released his inaugural album titled: “Traditionally Yours: Mi’kmaq Drums, Young and Old” and has travelled beyond Atlantic Canada to share the authentic Mi’kmaq culture outside of Mi’kma’ki. He is also a member of the Mi’kmaq band Stoney Bear.

(Folk Alliance International, n.d.)

Morgan Toney

Morgan Toney is a Mi’kmaq singer-songwriter/ fiddler from Wagmatcook First Nation. As an ambassador for the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund, Morgan helps build cultural awareness by educating non-indigenous people about his indigenous culture. His debut album, "First Flight”, combines traditional Mi’kmaq songs and Celtic Cape Breton fiddle, which he titled “Mi’kmaltic.” Morgan Toney’s passion for music has brought him closer to his family by participating in a tradition passed down through generations.

References